Climate Science 101: Climate Risk Scenarios and Net Zero for Investors (Part 1)

Learn about Climate Scenario Analysis: Global Reference Scenarios, IPCC Scenarios, IEA and other Reference Scenarios.

Hi All,

Do you like mountains? I do. I know it is a random question, but I hope we can have this beautiful nature with us as long as we can hold onto her. That was the inspiration for today's post.

Climate risk is becoming an increasingly important consideration for investors, businesses and policymakers alike, as evidenced by the Bank of England and ECB's recent climate risk stress testing and regulatory pressures following the Paris Agreement. In this post, we'll explore the topic of climate scenario analysis, including global reference scenarios, net-zero scenarios, and various reference scenarios from organizations such as the IPCC and IEA. Sorry, today's post is a bit long and dry, but understanding these concepts is crucial for anyone looking to make informed decisions around climate risk and ask meaningful questions as the models continue to evolve based on new regulations and more granular data sets becoming available from companies. So, bear with me and let's go!

As always, welcome feedback and contributions! Always looking for collaborators and inspiration for the next topic to cover.

Today's Key Concepts

1. What is a Climate Scenario Analysis?

2. What are 'Global Reference Scenarios'?

3. Net Zero and Climate Scenarios

4. IPCC Scenarios (RCPs and SSPs)

5. IEA and Other Reference Scenarios

6. Conclusion

Note) Transition and Physical Risk Scenario Analysis (ft. NGFS Example) will be covered in Part 2. The Climate Value at Risk (CVaR) + BOE and ECB's climate risk stress testing will be covered in Part 3.

I. What is a Climate Scenario Analysis?

🏈 Bottom line: Scenario analysis is a technique that involves creating narratives that depict possible future states of the world. While it has been used in academic research since the 1950s, it has also been applied by many large corporations and is now being widely used to analyze climate risk.

Below shows the NGFS's climate scenario framework example which is the basis of for many financial investors' and banks (incl. BOE and ECB)' climate risk stress testing scenarios.

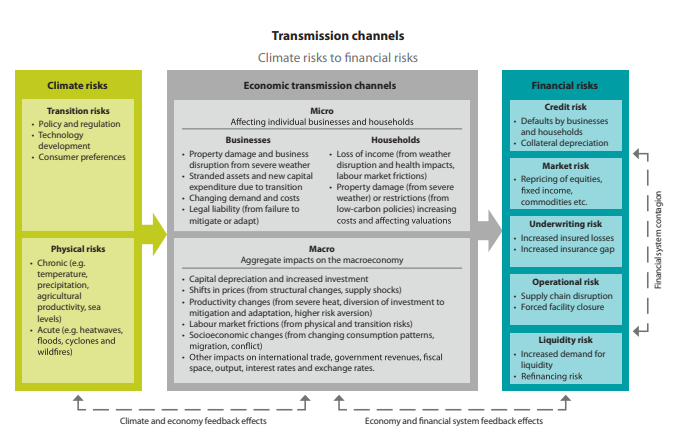

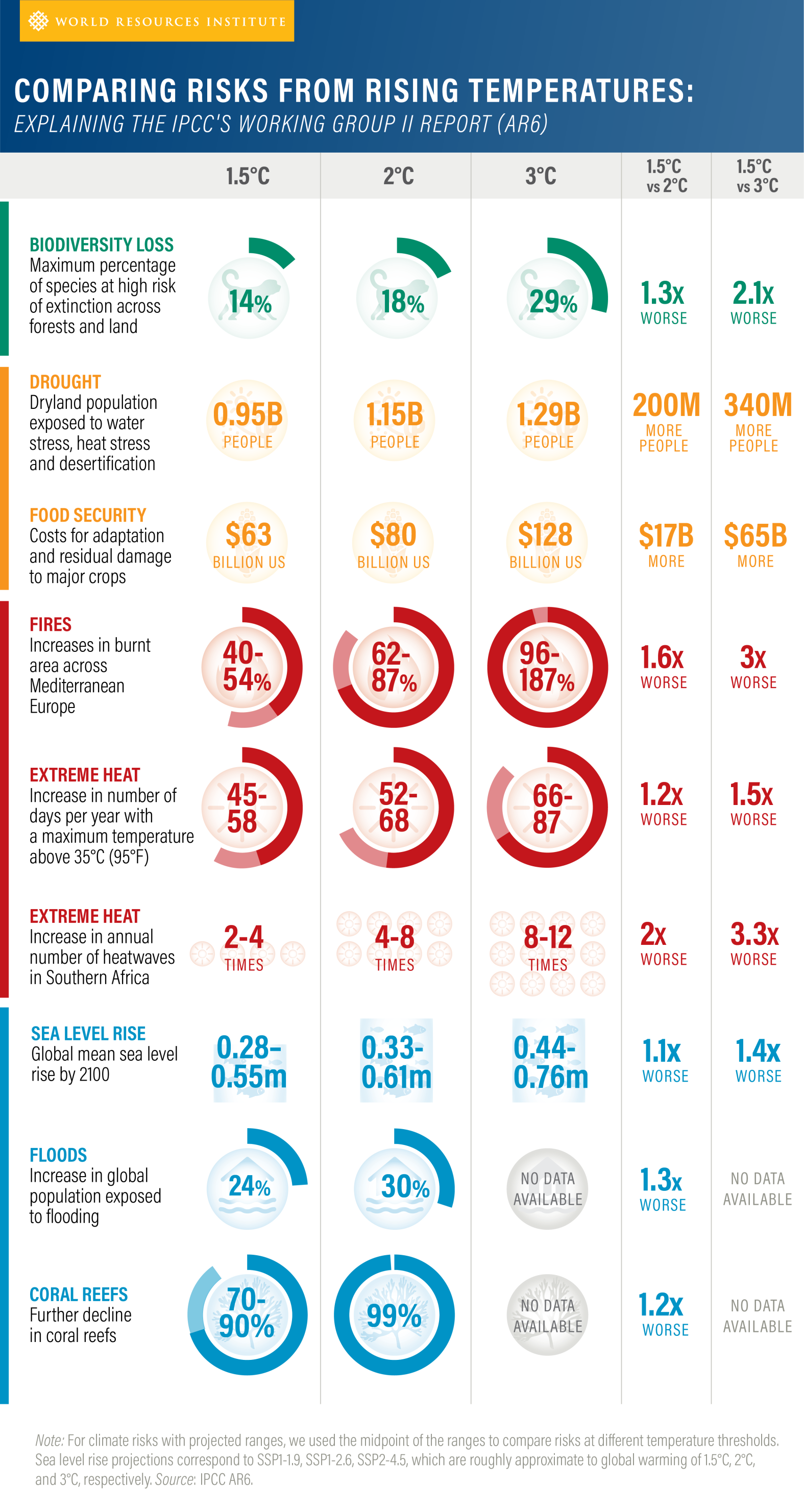

🏈 Bottom line: Climate risk is composed of two main elements- transition risk and physical risk.

- Transition risks will affect the profitability of businesses and wealth of households, creating financial risks for lenders and investors. They will also affect the broader economy through investment, productivity and relative price channels, particularly if the transition leads to stranded assets.

- Physical risks affect the economy in two ways.

- – Acute impacts from extreme weather events can lead to business disruption and damages to property. There is some evidence that with increased warming they could also lead to persistent longer term impacts on the economy. These events can increase underwriting risks for insurers, possibly leading to lower insurance coverage in some regions, and impair asset values.

- – Chronic impacts, particularly from increased temperatures, sea levels rise and precipitation, may affect labour, capital, land and natural capital in specific areas. These changes will require a significant level of investment and adaptation from companies, households and governments.

II. What are 'Global Reference Scenarios'?

🏈 Bottom line: To conduct climate scenario analysis, it is crucial to have agreed-upon and widely used projections of future emissions, often with socio-economic narratives attached. These projections are known as global reference scenarios and serve as a key input for climate scenario analysis.

The most widely used reference scenarios are from the IPCC, which includes representative concentration pathways (RCPs) and accompanying shared socioeconomic platforms (SSPs). These scenarios allow for greater nuance regarding societal and economic factors, as well as policy changes, to be incorporated into the RCPs. Other providers of reference scenarios include the International Energy Agency (IEA), Greenpeace, IRENA, and the NGFS.

III. Net Zero and Climate Scenarios

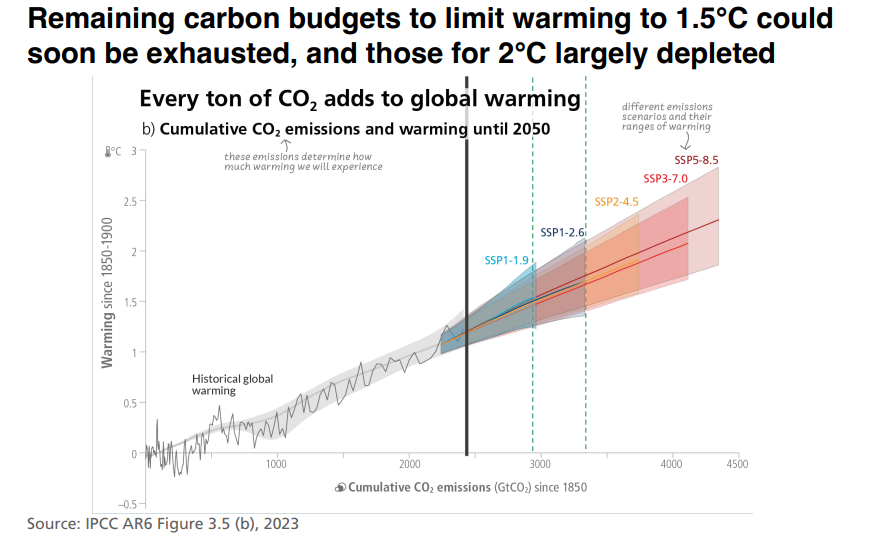

🏈 Bottom line: All scenarios that result in the stabilization of global temperatures, at whatever temperature and over whatever timeframe, end up at net zero.

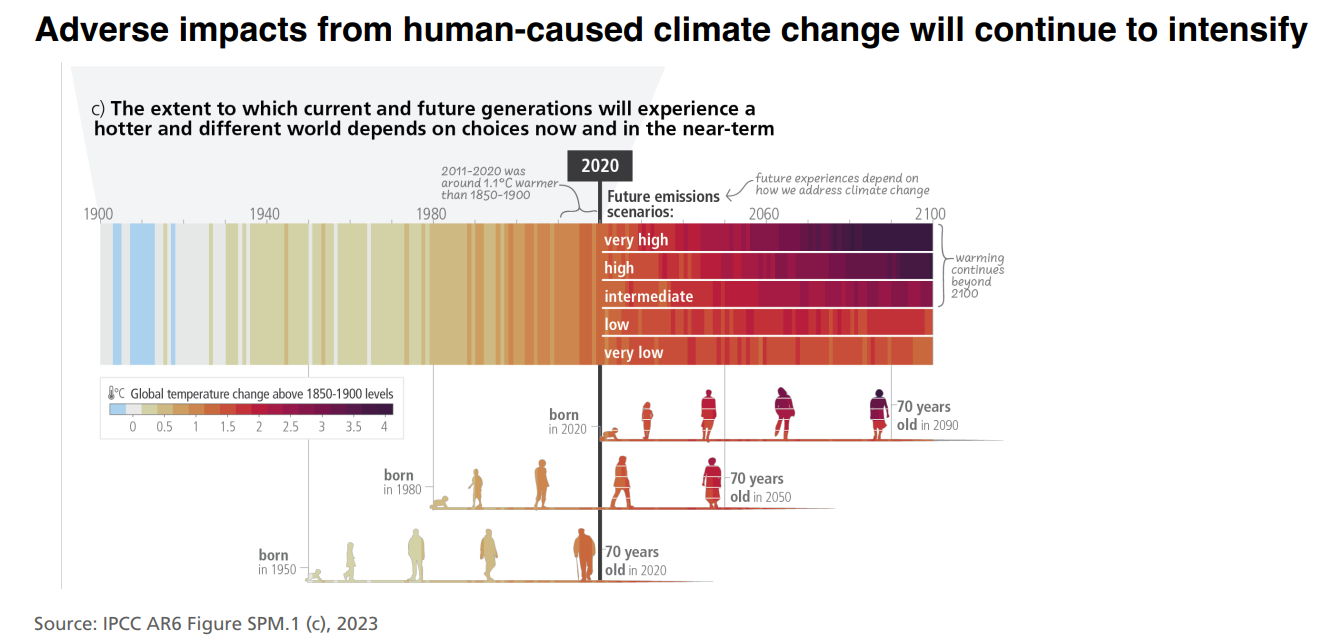

Net zero means reducing global emissions (“sources”) to zero in almost every sector of the global economy and balancing out any residual emissions that cannot be eliminated with removals (“sinks”) on an ongoing basis. To stabilize the climate at any given temperature, whether it is the Paris Agreement’s objective of holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C and pursuing efforts to limit temperature rises to 1.5°C, 2°C, 2.5°C, 3°C, or 4°C, we need to achieve net-zero carbon emissions in order to stabilize the stock of carbon in the atmosphere (IPCC, 2018).

To achieve net-zero emissions and stabilize the climate, we must reduce carbon emissions in every sector and extract carbon from the atmosphere at large scales using biological, chemical, and industrial processes. This is necessary because some sectors, like agriculture, will have residual emissions that are difficult to eliminate, and other sectors, like aviation, do not yet have viable zero-carbon alternatives.

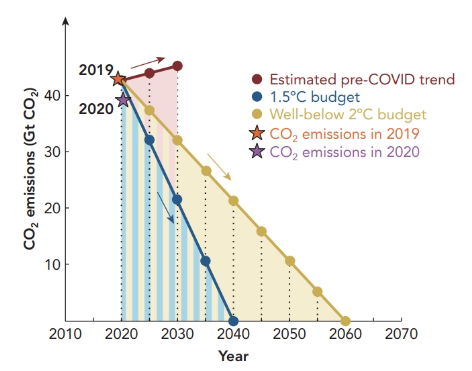

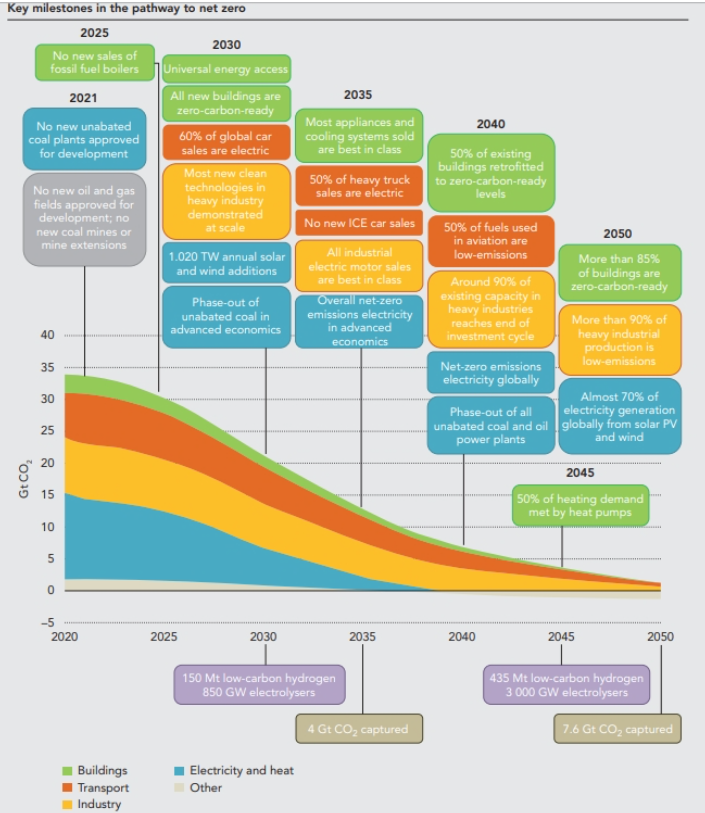

The below chart shows different pathways for stabilizing temperatures at 1.5°C or 2°C, respectively. Some scenarios assume we reduce emissions later or more slowly, and although we ultimately reach net zero, the emissions produced over a slower and later transition result in higher temperatures. In contrast, scenarios where action begins immediately and emissions decline quickly, usually with emissions halving by 2030 and net zero being achieved mid-century end up keeping a 1.5°C or 2°C outcome “alive.”

[Different net zero pathways result in different temperature outcomes]

All scenarios use some carbon removals to achieve the “net” in net zero. Some scenarios ambitiously assume new technologies will be quickly deployed at a sufficient scale to scrub carbon from the atmosphere, others use less generous assumptions about the deployment of carbon removal technologies. These assumptions are key to determining whether net zero is achievable and this is not without controversy as different carbon removals options result in different trade-offs and have costs that will need to be absorbed by society.

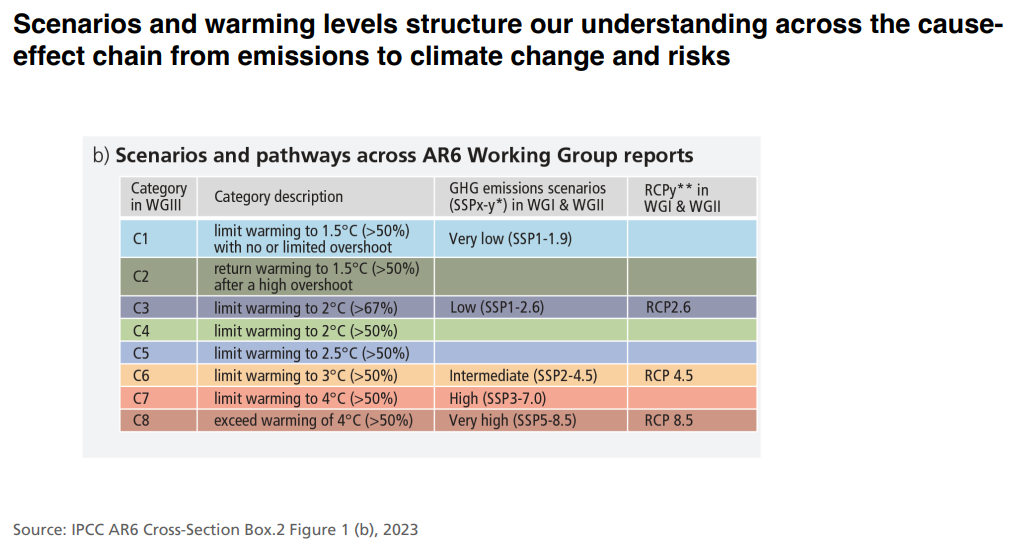

IV. IPCC Scenarios (RCPs and SSPs)

The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is key to the Earth’s climate, yet the concentration is being swiftly altered by human activity. Because of this fact, modeling and predicting the future trajectories of the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is arguably the single most important factor to understand—more so than having the physical parameters of a climate simulation model exactly correct. Indeed, given accurate emissions trajectory data, even simple climate models can perform quite well in predicting global warming. Because of this, there has understandably long been a focus among climate scientists in the IPCC to, if not definitively predict the single future path of emissions, at least lay out plausible, agreed-upon scenarios. These climate scenarios would then provide a common starting point for modelers. The first iteration of such scenarios was devised in the 1990s, with assumptions about population growth, economic growth, and emissions. From these beginnings among scientists, these kinds of scenarios have now become a crucial reference point for policymakers, corporate managers, and investors alike.

Q: What are 'Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs)'?

A: Current IPCC usage and modeling is based on representative concentration pathways (RCPs), which are agreed-upon, projected, plausible emissions pathways through 2100.

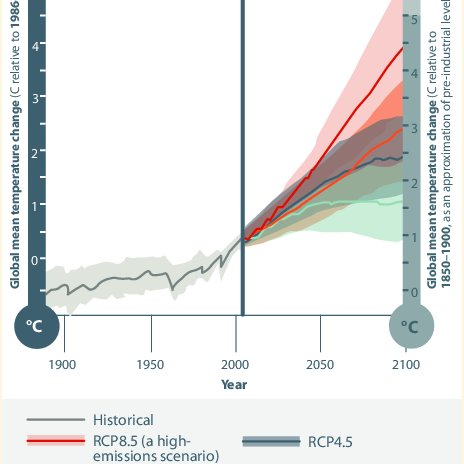

[RCP Scenarios examples]

These pathways represent different emissions projections under basic, plausible economic and social assumptions, while staying within physical constraints. The RCPs were constructed by back-calculating the amount of emissions that would result in a given amount of radiative forcing—the difference between solar radiation (energy) absorbed by the Earth and energy radiated back into space (as covered in this post)—that would then result in a given amount of warming. Because of this, the RCP names are based on the amount of radiative forcing measured in watts/meter squared (m2), and they do not correspond neatly with the anticipated amount of warming in degrees Celsius.

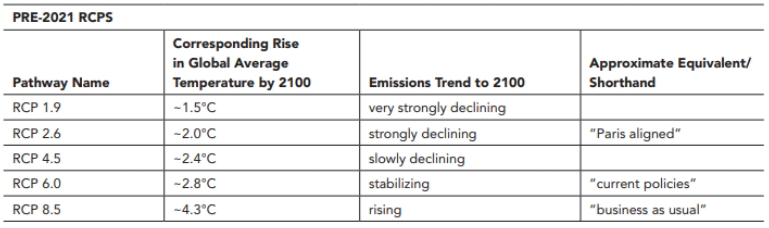

The table below lists the RCPs; the corresponding approximate, global average temperature rise by 2100; and the shorthand, if used. The most widely used models tend to be RCP 2.6 and RCP 8.5. RCP 2.6 is used as a shorthand for reaching Paris goals (of limiting warming to below 2°C) by drastically cutting emissions. RCP 8.5, sometimes called “business as usual,” and sometimes, confusingly enough, used as a “worst-case scenario,” is a scenario that assumes continued rising emissions, leading to much higher levels of warming.

RCPs, while originating with the IPCC, can now be found in everything from financial regulatory reports to commercially available climate risk tools meant for corporations. The RCPs that were current at the time of writing are being updated to include socioeconomic factors more explicitly.

Q: What are the 4 RCPs?

A: The four RCPs range from very high (RCP8.5) to very low (RCP2.6) future concentrations. The numerical values of the RCPs (2.6, 4.5, 6.0 and 8.5) refer to the concentrations in 2100.

Q: What are 'Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs)'?

A: The RCPs did not originally include a socioeconomic “narrative” but only emissions trajectories calculated using certain assumptions about energy use. Instead, shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) have been developed subsequently to be used in conjunction with the RCPs. SSPs are intended to provide plausible scenarios for how the world evolves in areas such as population, economic growth, education, level of globalization, level of urbanization, and the rate of technological development.

The five SSP narratives range from better to worse climate change outcomes.

- SSP-1 sketches out a scenario of a significant focus on sustainability;

- SSP-2 is a “business as usual” scenario;

- SSP-3 involves regional rivalry between countries;

- SSP-4 has a high degree of inequality; and

- SSP-5 posits fossil-fuel development.

| SSP1 | Sustainability – Taking the Green Road (Low challenges to mitigation and adaptation) The world shifts gradually, but pervasively, toward a more sustainable path, emphasizing more inclusive development that respects perceived environmental boundaries. Management of the global commons slowly improves, educational and health investments accelerate the demographic transition, and the emphasis on economic growth shifts toward a broader emphasis on human well-being. Driven by an increasing commitment to achieving development goals, inequality is reduced both across and within countries. Consumption is oriented toward low material growth and lower resource and energy intensity. |

| SSP2 | Middle of the Road (Medium challenges to mitigation and adaptation) The world follows a path in which social, economic, and technological trends do not shift markedly from historical patterns. Development and income growth proceeds unevenly, with some countries making relatively good progress while others fall short of expectations. Global and national institutions work toward but make slow progress in achieving sustainable development goals. Environmental systems experience degradation, although there are some improvements and overall the intensity of resource and energy use declines. Global population growth is moderate and levels off in the second half of the century. Income inequality persists or improves only slowly and challenges to reducing vulnerability to societal and environmental changes remain. |

| SSP3 | Regional Rivalry – A Rocky Road (High challenges to mitigation and adaptation) A resurgent nationalism, concerns about competitiveness and security, and regional conflicts push countries to increasingly focus on domestic or, at most, regional issues. Policies shift over time to become increasingly oriented toward national and regional security issues. Countries focus on achieving energy and food security goals within their own regions at the expense of broader-based development. Investments in education and technological development decline. Economic development is slow, consumption is material-intensive, and inequalities persist or worsen over time. Population growth is low in industrialized and high in developing countries. A low international priority for addressing environmental concerns leads to strong environmental degradation in some regions. |

| SSP4 | Inequality – A Road Divided (Low challenges to mitigation, high challenges to adaptation) Highly unequal investments in human capital, combined with increasing disparities in economic opportunity and political power, lead to increasing inequalities and stratification both across and within countries. Over time, a gap widens between an internationally-connected society that contributes to knowledge- and capital-intensive sectors of the global economy, and a fragmented collection of lower-income, poorly educated societies that work in a labor intensive, low-tech economy. Social cohesion degrades and conflict and unrest become increasingly common. Technology development is high in the high-tech economy and sectors. The globally connected energy sector diversifies, with investments in both carbon-intensive fuels like coal and unconventional oil, but also low-carbon energy sources. Environmental policies focus on local issues around middle and high income areas. |

| SSP5 | Fossil-fueled Development – Taking the Highway (High challenges to mitigation, low challenges to adaptation) This world places increasing faith in competitive markets, innovation and participatory societies to produce rapid technological progress and development of human capital as the path to sustainable development. Global markets are increasingly integrated. There are also strong investments in health, education, and institutions to enhance human and social capital. At the same time, the push for economic and social development is coupled with the exploitation of abundant fossil fuel resources and the adoption of resource and energy intensive lifestyles around the world. All these factors lead to rapid growth of the global economy, while global population peaks and declines in the 21st century. Local environmental problems like air pollution are successfully managed. There is faith in the ability to effectively manage social and ecological systems, including by geo-engineering if necessary. |

The SSP base scenarios deliberately do not include climate policies. The reasoning is that the SSPs can be combined with different RCPs to explore the climate policy options and assumptions that are necessary to limit global warming to a particular target level. Specifically, shared climate policy assumptions capture key policy attributes such as the goals, instruments, and obstacles of mitigation and adaptation measures, and they introduce an important additional dimension to the scenario matrix architecture.

For instance, RCP2.6 and RCP1.9 are both possible to achieve under the baseline SSP1 assumptions, but with tighter climate mitigation policies in the latter. RCP2.6 is a plausible emissions pathway under both SSP1 and SSP2, but the underlying socioeconomic drivers and outcomes are different.

Having the SSPs alongside, but separate from, RCPs allows the two to be mixed and matched. This permits the exploration of climate policy options and their impact on energy use, land use, emissions, and economic activity in a matrix-type format. To compare matrix rows is to compare different levels of climate policy stringency (as rows are different RCPs); to compare matrix columns is to compare different baseline socioeconomic situations, but the same level of climate policy stringency (different SSPs) (see graph).

However, not all RCPs are achievable under all SSPs—a high-mitigation scenario is not feasible under the SSP3 “regional rivalry” assumptions. The models that can assess the combination of social, economic, energy, emissions, and climate factors are called integrated assessment models.

As important as the IPCC’s RCPs and SSPs are as a reference point, the IPCC is not the only organization to have put out scenarios. Several other organizations’ projections are also used widely by governments, companies, and financial institutions.

V. IEA and Other Reference Scenarios

🏈 Bottom line: There are a limited number of global, macroeconomic climate scenarios and predicted emissions trajectories from organizations beyond the IPCC that are used widely enough to be common reference scenarios.

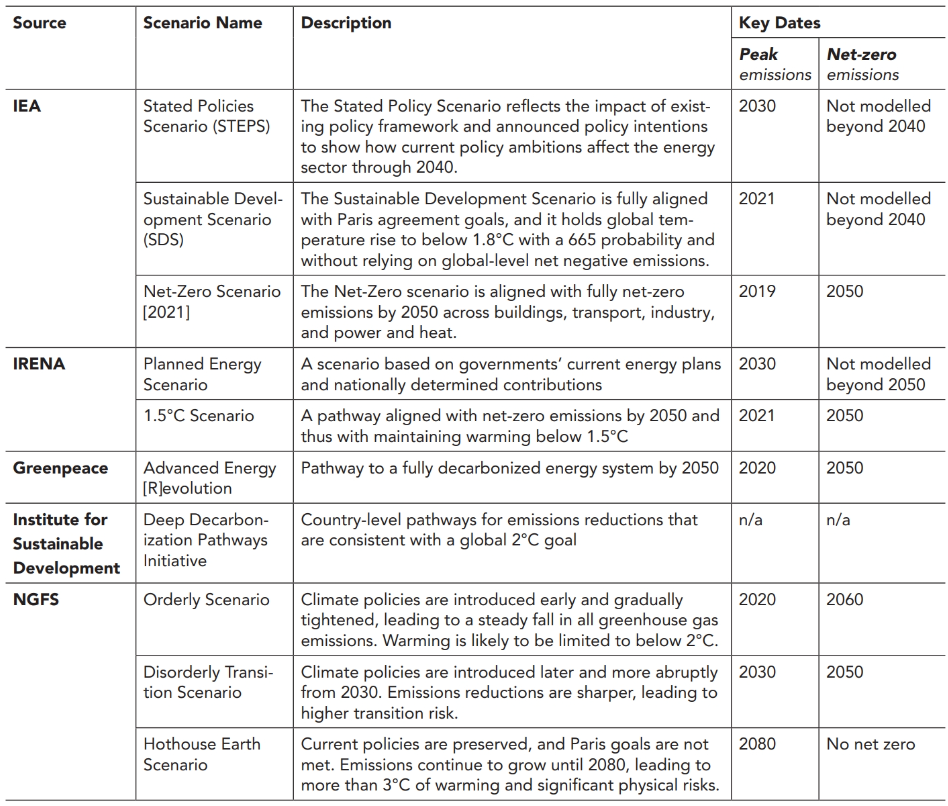

Most important among these are the scenarios developed by the International Energy Agency (IEA). The IEA’s two core scenarios are the 1) Stated Policies Scenario, which reflects existing policy frameworks and announced policy intentions, and 2) the Sustainable Development Scenario (SDS), which combines climate and social targets and limits warming to 2°C in line with Paris targets.

The IEA has also modeled net-zero emissions by 2050 scenarios. After years of being criticized for consistent under-estimation of the potential for renewables and expecting the persistence of fossil fuels, the IEA’s report on net-zero of May 2021, its most comprehensive up to that point, laid out a much more ambitious path to the achievement of net-zero (see box). The IEA has occasionally modeled other scenarios as well, such as a delayed economic recovery scenario in 2020 in response to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Besides the IEA, there are a handful of other energy transition and climate scenarios in wide use such as the sector-specific scenarios of the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project (DDPP), run out of the Institute for Sustainable Development, a French think-tank. In the financial sector, the scenarios developed by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), which is composed of central banks and financial supervisors, are commonly used, esp. the Bank of England and ECB's stress testing. While their materials have been primarily intended for central banking and financial supervision, private-sector financial institutions have also made use of NGFS scenarios. All of these scenarios can then be plugged into various modeling ensembles to estimate impacts. As an example, central banks and private-sector banks making use of the NGFS scenarios have tended to use the REMIND model, a holistic model developed by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). A more detailed analysis of key current reference scenarios is below.

VI. Conclusion

Although scenario analysis often begins with reference scenarios, several decisions must be made to perform scenario analysis effectively. This includes setting various parameters and assumptions, choosing analytical tools, and defining outputs. By using global reference scenarios such as RCPs and SSPs, along with net zero scenarios and other reference scenarios from organizations like the IEA, investors, businesses and policymakers can develop effective strategies to manage both transition and physical risks associated with climate change. Climate scenario analysis is an essential tool for addressing the urgent global challenge of climate change.

In closing,

Oprah Winfrey once said that intention is everything.

"The energy of your intention is what determines your life. Most people don't think about their intention. They just think about what they want to do. Most people don't think about why they want to do it, but what's gonna come back to them."

I wanted to share some pictures from the Dolomites that my friends sent over. Mother Nature is an incredibly beautiful and sacred place, and while working in the city and sifting through various news and data about the 'climate' stuff, I sometimes forget about her grace, even though the whole reason WHY I do what I do is to honor 'her' and 'us'. I hope to one day experience the grace of the Dolomites firsthand and be embraced by her energy to rejuvenate myself. I hope you can also feel the serene energy of the Dolomites through the screen.

Breathe in. Breathe out. and keep going.

Photo Credit: @OurStorytoTell.

![Sustainable/Impact Investing] Regulations Cheatsheet - State of Play (December 2025)](/content/images/size/w720/2025/12/Screenshot-2025-12-08-073043.png)

![Obsidian Brief] When Money Becomes Software: AI, Stablecoins & Bitcoin — Implications for Sustainable and Impact Investing](/content/images/size/w720/2025/12/Gemini_Generated_Image_dppem0dppem0dppe.png)

![Sustainable/Impact Investing] Building for Planetary Renewal - Urban Sequoia (A lecture by Mina Hasman, Sustainability Director at SOM)](/content/images/size/w720/2025/10/Screenshot-2025-10-30-221501.png)